Lemons on the Side of the Road

6 March 2023You Can’t Beat the Bush!

5 April 2023

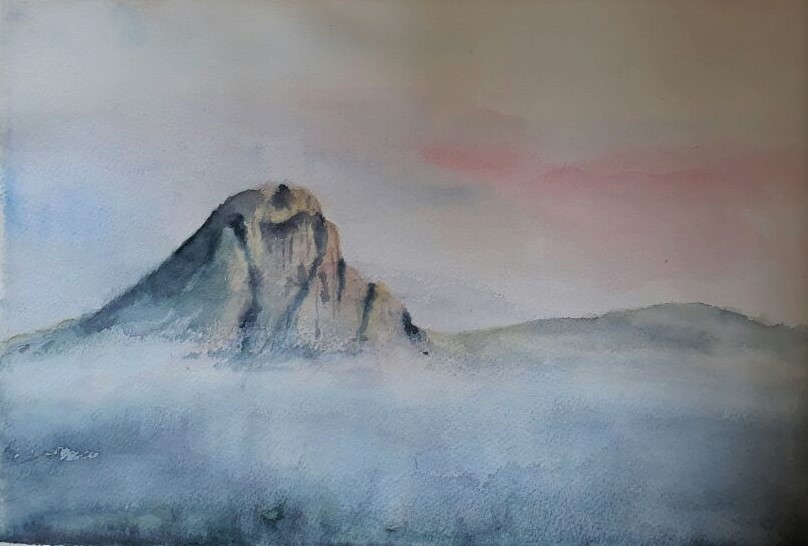

It was a beautiful morning, summer sunshine on a lush green landscape, soft white clouds embracing the mountain tops – I felt a twinge of nostalgia as I drove towards the land of my birth, Eswatini. Memories intruded: coming home from boarding school, from Johannesburg when I was a working student, and then from Zimbabwe where I spent the first year of my marriage.

There is a certain spot that lines up with the mountains, ragged and majestic peaks, part of the Drakensberg range, that form a natural border between South Africa and Eswatini. It was the place where we would all exclaim: “Nearly home!” I pulled over to take a picture, to share with another old Swazi dweller now living in London. A couple doing their washing in a basin on the other side of the road watched me curiously – I waved, they waved back hesitantly.

Through the border and the next photographic stop was a spot on the highway above the capital city of Mbabane, where a long descent begins into the heartland of Eswatini – the Ezulwini Valley. The dreaded Malagwane Hill. It once had a place in the Guinness Book of Records for the most per capita deaths as its bends and steep sections caused accident after accident, many from failed brakes. There was even talk of a ghost that stalked the mountain, seeking blood for some indiscernible reason.

Ezulwini, or Valley of Heaven in English, is defined by three famous peaks: Sheba’s Breasts, given fame in Rider Hagar’s novel, “She”; Nyonyane, or Execution Rock, where dire punishments were meted out for the smallest of infringements – men hurled to their death down the precipitate rockface. They looked like little birds as they fluttered to their death – hence Nyonyane – Little bird. Facing these two, the Mdimba Range, the penultimate peak home to the cave where the kings of Swaziland reign in perpetuity.

It is a magnificent view from Mbabane, although I couldn’t stop in the optimal spot for a good picture.

After a night in the farmlands of Malkerns, I headed north to Pine Valley, another mountain guarded sanctuary on the other side of Mbabane, dominated by the turbulent Umbuluzi River, more rugged than Ezulwini, not as spacious, but equally impressive. It is home to Sibebe Rock, first cousin to the famous Ayres Rock in Australia.

The sunshine had given way to clouds, the temperature had dropped some 10 degrees, a feature of this part of the world – swelter one day, shiver the next – a perfect day to take the dogs for a walk. I set off with my son and grandson, who bemoaned the amount of litter and that we had not brought a black bag with us to fulfil our community duty by collecting it. The only thing a grandma, or the vernacular ‘Gogo’ (pronounced Gawgaw), could do to distract was tell a story, identifying birds and flowers not being that appealing to an eight-year-old lad.

The walk took me back to 1979. In a moment of insanity, I allowed myself to be persuaded to invest in a small country hotel in Piggs Peak, a hamlet in the far north of Eswatini. A horse lover, I thought providing tourists with outrides into the rural countryside was a great idea, so I bought three horses from an old friend, Liz Reilly of Mlilwane Game Sanctuary. Two were fully broken, one accepted a saddle but had not been mounted.

Horseboxes were an unheard-of luxury in Swaziland in those days, so I hired a cattle truck to bring them up the horrific Malagwane to Mbabane. It was a nightmare trip, with one animal determined to escape over the sidebars while I dangled desperately from his halter to stop him. The thought of a similar trip through the more precipitous Komati Valley, over a gravel road, was untenable. Much better to ride them over.

We had a few weeks to prepare the horses, get ourselves fit for the 60-mile hike across rivers, through valleys and over steep mountains. A couple of friends offered to ride alongside me, and another agreed to accompany us in my car with sleeping bags, equine and human provisions, and general paraphernalia. We worked out a route through this same Pine Valley that would bring us out at a midway point on the road to Piggs Peak, part way down the first part of the Komati Valley.

There was a kraal on the mountainside where we hoped to overnight the horses; we would sleep under the stars in our sleeping bags.

The first indication that the day would not be as adventuresome as we imagined was when Hunki Dori, the unbacked gelding, refused point blank to cross the first stream we came to. Granted the bridge was made of poles trussed together, but he came from Mlilwane where all the bridges were made this way. We tried lifting his feet and putting them on the bridge, we led the other two horses backwards and forwards to lead him across until we were all dizzy.

Right, through the water it is. We found a shallow crossing, good footing and led him forth. He took one look at the water, fixed me with a glare that said, “try me!” and planted all four feet – 800 kgs of solid resistance. Two and a half hours later, he had been backed, and we were on the other side of the river.

The rest of the day passed moderately well. Every stream crossing was a challenge, but we won and eventually at about 5 in the evening, after 12 hours on the road, we arrived at the junction with the road to Piggs Peak. The kraal was not far off.

We had noticed a storm, quite serious looking, behind us, but it was miles away over the Lowveld, and travelling south of us. We thought. Until the wind changed direction. Within minutes, the light was sucked into darkness starkly broken by blinding flashes of lightning. I have never heard such a racket, thunder, driving rain, gusting wind. And then hail. Hail such as we had seldom seen. The size of tennis balls.

We grabbed the sleeping bags to try and cover the horses, who were freaking out. We were on a section of road with a high bank, so tried to take shelter under it, but an electric pole above us kept being struck by lightning, resulting in metres long flashes zinging out from it.

My horse reared, broke free and disappeared into the gloom of the hell breaking over us. There was a steep bank, I imagined he had broken his back, or a leg and I couldn’t see or find him. My one companion fell – he’d been in an accident and was recovering from kidney damage. We tried to get him into the car while hanging on to the other two horses. He slipped and was lying face down on the back seat, his damaged kidneys exposed and cruelly pummelled by the hail.

Something nudged me as I tried to lift him onto the seat. Margley had returned. Thank God. Kevin finally safe, our driver grabbed one horse and we set off for the kraal. By now the ground was covered in about 18 inches of ice, we were numb to the pelting hail, and still the storm raged.

Part way down the road, looking for the track to the kraal, I felt as if someone had whacked my hard hat with a mallet. All went quiet. The horses stood still, heads bowed, and as I looked at Keith and Bindy, they too were standing quietly unmoving next to their charges. We must be dead, I thought. Maybe when you first die, you are in the same place as when it happened. Now what? I looked nervously over the brow of the mountain, wondering whether an angel or demon was coming for me. I’d said some pretty bad things to God, so was rightly nervous.

We weren’t dead. The hail stopped, the thunder rolled away leaving softer rain and newly forged streams gushing down the mountainside. Our hearing returned. It was decided I should take Kevin to Piggs Peak to the hospital and leave the other two to manage the horses. They went to the roadwork camp at the top of the mountain, where they found an Italian who knew all about horses and he happily took charge of them for the night.

It was the worst hailstorm in Swaziland in thirty years, one that caused millions of rands worth of damage.

And we lived through it!

Shortly after that, I made a commitment to serve the Lord Jesus Christ. I figured if He loved me enough to pelt me with large hailstones to get my attention, and still save my bacon after all the names I called Him, I should maybe give Him a chance, listen to what He had to say to me. It was the best decision of my life.

My grandson was suitably impressed with my tale and responded by demanding photographs of himself under an extra section of the new bridge that was left on the bank. If I stooped low enough it would look as if he was holding up the massive structure. It also made a good frame for another view of Sibebe.

It was a fun afternoon and I now have new memories, good ones, to carry forward.